Astana is anxious to expand bilateral relationships and attract more investment into its economy of $128 billion through enhanced ties with the United Kingdom.

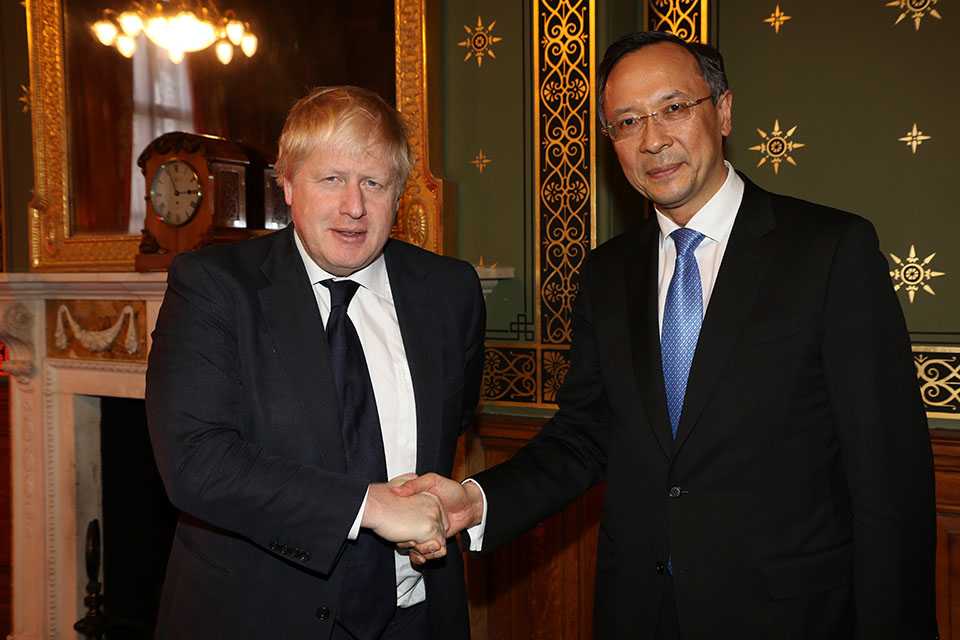

“Kazakhstan will continue to strengthen its strategic partnership with the U.K. in order to modernize the economy, increase investment and trade exchange between the two countries, following the agreements reached at the highest level,” Kazakhstan’s Foreign Minister Kairat Abdrakhmanov said on November 21, during what was a two-day visit to London that included meeting his British counterpart Boris Johnson.

Maksim Kaznacheyev, an expert based in Almaty, sees Abdrakhmanov’s visit as critical to Kazakhstan’s connection to outside markets and maintaining the interests of British companies in Kazakhstan.

“Some major assets in Kazakhstan are owned by British companies, in the realms of oil and gas and metallurgy. Therefore cooperation through diplomatic channels is a supporting factor that keeps the interest of British investors in the Kazakh economy,” Kaznacheyev told Caspian News.

In London, Abdrakhmanov met with representatives from Metalysis Ltd., which has been cooperating closely with Kazakhstani officials to develop high-value metals and alloys for additive manufacturing in Central Asia’s largest country and economy.

Abdrakhmanov’s visit also included meetings with the financial investment company United Green, as well as the Independent Power Corporation, Britain’s leading power developer and power plant operator, to discuss the potential of possible investments into Kazakhstan’s non-oil areas, namely in the realm of renewable sources.

Trade and investment connections between Kazakhstan and the U.K. run deep and are represented by groups such as the British-Kazakh Society. British direct investments in Kazakhstan were $12 billion between 2005 and 2016, and the U.K. is the country’s sixth largest investor.

Investments involve more than 800 enterprises. The largest is Royal Dutch Shell, a stakeholder in Kazakhstani oil and gas projects such as the North Caspian (Kashagan field) and the Caspian Pipeline Consortium, as well as Ernst & Young, a multinational professional services firm headquartered in London. Other companies present in Kazakhstan include Rolls Royce, BAE Systems, PwC, KPMG and WorleyParsons.

In 2016, bilateral trade was worth over $1.2 billion. Exports from the U.K. were worth $889 million and imports reached $372 million, according to Kazakhstan’s Statistics Committee. Kazakhstan provides the U.K. mostly with crude oil and oil-based products, metals and precious metals, including silver; food, equipment, manufactured goods and pharmaceuticals. In turn, Kazakhstan absorbs U.K.-manufactured machines, electrical equipment, including sound recording and sound reproducing equipment.

Abdrakhmanov’s recent visit to London comes after officials had signed more than 20 agreements, worth $5 billion, in 2015, which included deals to construct four gas turbine power plants and develop the steel production industry in Kazakhstan.

Kaznacheyev told Caspian News that Kazakhstan’s interest in developing its economy beyond the oil and gas sectors stems from recent economic downturns.

“Kazakhstan has had quite difficultly surviving the economic crisis related to the decline in prices of hydrocarbons, and therefore it has been looking for additional investments, including those from the U.K.,” Kaznacheyev said.

Although Kazakhstan sits atop some of the world’s largest reserves of fossil fuels and ranks tenth in terms of world oil exporters, its economy has floundered in times when global prices have slumped.

When the price of crude fell below $35 per barrel in 2015, Kazakhstan’s economy was hit hard. A drop in crude oil prices pushed Astana’s national currency, the tenge, to use a floating exchange rate whereby its value is allowed to fluctuate in response to foreign-exchange market mechanisms.

Because oil exports make up nearly 70 percent of Kazakhstan’s foreign trade and more than half of the state budget, officials in Astana became aware that the economy suffers from an overreliance on oil and extractive industries. In recent years, they have taken steps to diversify the economy by targeting sectors such as transportation, telecommunications, petrochemicals, pharmaceuticals and food processing.

In 2012, President Nursultan Nazarbayev introduced “Kazakhstan 2050”, a roadmap for diversifying the country’s production and export base. Three years later, he unveiled “100 concrete steps for implementing 5 institutional reforms”, a plan that outlined how the country would go about undertaking deep economic, social, judicial and political reforms. Almost two thirds of the planned changes related to business, including the development of modern and diversified energy projects that would stimulate foreign investment.

The U.K.’s involvement in Kazakhstan has helped play a part in economic diversification, but mutual ties go beyond British pounds, tenge, dollars and cents. Experts say that the U.K. considers Kazakhstan a significant player within the framework of the Eurasian Economic Union – a trade bloc comprised of Kazakhstan, Russia, Armenia, Belarus and Kyrgyzstan – and a valuable mediator in strained relations between the West and Russia.

“Given the complexities in relations with Russia related to sanctions, [the U.K.] considers [Kazakhstan] as an intermediary in relations with the Kremlin,” Maksim Kaznacheyev told Caspian News. “Some initiatives can be roughly discussed with President Nazarbayev so that later it is easier to build political relations with the Kremlin’s political elite.”

In 2014, a series of Western sanctions were slapped on Russia due to what some countries believed was a Russian military intervention in Ukraine, as well as Russia’s annexation of Crimea. In 2016, the European Union prolonged the validity of its sanctions until January 31, of next year, as a maneuver to punish Moscow for its disobedience in regards to the Minsk agreements aimed at alleviating the conflict in Ukraine.

Armenian sappers commenced on Monday mine-clearance operations in the territories adjacent to the Saint Mary Church in village of Voskepar (Armenia...

Armenian sappers commenced on Monday mine-clearance operations in the territories adjacent to the Saint Mary Church in village of Voskepar (Armenia...

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov has reasserted that Moscow has no intentions to stop the fighting in Ukraine, even if peace talks commence.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov has reasserted that Moscow has no intentions to stop the fighting in Ukraine, even if peace talks commence.

Iran has refuted reports of alleged damage to Shimon Peres Negev Nuclear Research Centre located southeast of Dimona, Israel, during the recent air...

Iran has refuted reports of alleged damage to Shimon Peres Negev Nuclear Research Centre located southeast of Dimona, Israel, during the recent air...

Iran and Pakistan have signed eight cooperation documents in various fields, and agreed to strengthen ties to fight terrorism in the region.

Iran and Pakistan have signed eight cooperation documents in various fields, and agreed to strengthen ties to fight terrorism in the region.