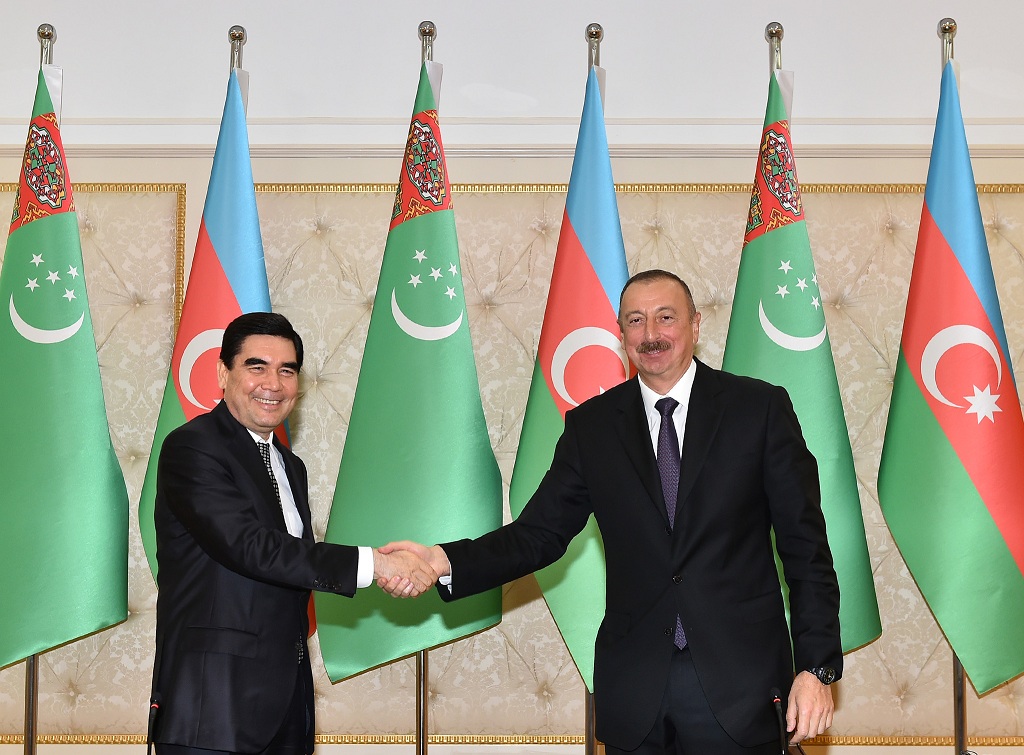

Turkmenistan’s President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow is on a two-day visit to neighboring Azerbaijan, where he has already met with President Ilham Aliyev and is expected to discuss how Turkmenistan can get in on one of the largest infrastructure and energy projects ever built across Asia and Europe.

For all the similarities and geographical proximity to one another – Azerbaijan lies along the west coast of the Caspian Sea, Turkmenistan on the east – the two have had their fair share of differences since becoming independent after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

How to partition the world’s largest lake lay at the root of any dispute over the vast hydrocarbon deposits beneath the Caspian Sea. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, determining the legal status of the sea has been a problematic issue for all five of its littoral states, including Russia, Iran, and Kazakhstan.

The lack of consensus on each state’s legal rights to the waters, and what lies beneath them, has prevented the development and exploitation of disputed oil and gas fields, including the offshore oil deposit known as the Kapaz field in Azerbaijan, and Sardar in Turkmenistan, which holds an estimated 150 million barrels.

Russia and Kazakhstan signed an agreement in 1998 on the delineation of the northern part of the Caspian Sea and a protocol agreement in 2002 to exercise their sovereign rights for subsoil use. Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan followed with an agreement and protocol of their own.

By 2003, all three countries reached an agreement on the demarcation of adjacent sections of the sea. Russia, Kazakhstan, and Azerbaijan have advocated for dividing the seabed into national sectors, but leaving the surface – the water itself – for general use.

Iran and Turkmenistan, on the other hand, support dividing the waters equally, with each littoral state owning 20 percent. With a patchwork of oil and gas deposits irregularly located under the seabed, dividing the Caspian often runs into conflicting national interests.

Despite any differences, however, bilateral relations between Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan have trotted forward over the years, in part because the relationship has been supported at the highest levels of government.

Berdimuhamedov, who was sworn in as Turkmenistan’s second president in 2006, first visited Azerbaijan in May 2008, at which time any outstanding disputes with Azerbaijan appeared to have receded. President Aliyev followed with a visit to Ashgabat in November that same year. Issues like the division of the Caspian were put on the back burner, if for nothing else than the sake of rapprochement.

"The issue of the Caspian’s division into national sectors is currently not the first, but the last point on the agenda of the two countries," President Aliyev said in 2010.

Turkmenistan has struggled to capitalize on its offshore oil and gas wealth, with experts citing excessive red tape and corruption as reasons deterring investors, but its potential is undisputed. Turkmenistan’s section of the Caspian Sea contains around 1.1 billion barrels of liquid hydrocarbons and 255 billion cubic meters of natural gas in proven and probable reserves, according to a 2012 US Department of Energy estimate.

Berdimuhamedow’s latest visit, which wraps up today, indicates that at the very least Ashgabat understands Azerbaijan’s strategic importance. Good relations with Baku are critical to Turkmenistan, as officials in Ashgabat look to diversify the country’s gas export routes beyond Russia's pipeline network and sell gas to Europe via pipes that extend westward through Azerbaijan.

Political expert Elxan Sahinoglu says Turkmenistan is looking for opportunities via alternative routes to Russia.

“The dependence on Russia costs Turkmenistan dearly. Russia’s Gazprom purchases Turkmen gas whenever it wants, and stops the operation of the gas pipeline whenever it wants,” Sahinoglu told Caspian News. “This aggravates Turkmenistan’s economic situation. In order to get rid of dependence on the Russian gas pipeline, it is important for Ashgabat to agree to the construction of a pipeline along the Caspian seabed.”

In 2010, newly developed pipelines brought Turkmenistani gas to China and northern Iran, effectively ending Russia’s monopoly on Turkmenistan’s gas exports. But just last year Russia and Iran halted purchases, making China Turkmenistan’s sole buyer. With 25 percent of Turkmenistan’s gross domestic product tied to hydrocarbon exports, the bulk of which is natural gas going to China, officials also recognize that the country has become too dependent on Beijing.

Ashgabat is exploring two initiatives to bring gas to new markets: the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India gas pipeline, and the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline that would ultimately carry gas to Europe after cutting horizontally across the Caspian Sea between Turkmenbashi and Baku. The project could plug Turkmenistan’s more than 7.5 trillion cubic meters of proved natural gas reserves – the sixth largest on the planet – into the larger Southern Gas Corridor, which cuts through Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkey, Greece, and Albania before ending in southern Italy. The corridor is expected to start delivering Caspian gas next year.

As the world’s eleventh largest natural gas producer and seventh largest exporter, Turkmenistan’s potential as an energy supplier that is looking to diversify its export markets, and cut out Russia in the process, lies with Europe, which is energy dependent for as much as 53 percent of its needs.

“In order to build a gas pipeline along the Caspian seabed, Turkmenistan should join efforts with Europe, Turkey and Azerbaijan,” Sahinoglu said.

Turkmenistan’s lagging behind in being a global exporter of hydrocarbons is to a large extent its own doing. Ashgabat has long resisted the regional trend of pursuing a multi-vector foreign policy that balances between Russia, China, and the West. Permanent neutrality has resulted in Ashgabat avoiding membership in all major multilateral integration projects in the area, typically led by Russia, such as the Collective Security Treaty Organization – the post-Soviet world’s response to NATO – and the Eurasian Economic Union, its response to the European Union. Turkmenistan also lies outside the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the CIS Free Trade Area, and the GUAM Organization for Democracy and Economic Development. Furthermore, Turkmenistan is the only Central Asian state that is not a member of the seven-member Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

Instead, Ashgabat chose the path of permanent neutrality, a status the UN endorsed in 1995. Its neighbors - Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan - all have ample supplies of gas and compete with Ashgabat for access to gas markets, as does Russia. These countries generally have more favorable geographic locations than Turkmenistan for exporting hydrocarbons and are focusing on building their own pipeline infrastructures to export their gas.

On Tuesday, at a reception held for Berdimuhamedow, President Aliyev stressed Azerbaijan’s intent to cooperate with Turkmenistan in the energy sector.

“We intend to further deepen our work in this area, and there are all the possibilities for that,” Aliyev said.

In the first half of 2017, the trade turnover between Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan increased by over 40 percent compared to the same period last year. Berdimuhamedow suggested conducting a joint analysis of the state of bilateral trade, with the hope of expanding cooperation in areas like agriculture, infrastructure, petrochemicals, gas and electric power generation, to increase turnover further.

The Islamic holy month of fasting, Ramadan comes to an end this week with the celebration of a joyous festival called Eid (meaning “festival” in Ar...

The Islamic holy month of fasting, Ramadan comes to an end this week with the celebration of a joyous festival called Eid (meaning “festival” in Ar...

Iran's senior military leaders described the drone and missile attack on Israel on April 14 night as “successful".

Iran's senior military leaders described the drone and missile attack on Israel on April 14 night as “successful".

Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi warned Israel that it would face a "real and extensive" response if it makes any "mistake" following Tehran’s missi...

Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi warned Israel that it would face a "real and extensive" response if it makes any "mistake" following Tehran’s missi...